Conserving Our Heritage Sites

Conservation starts with understanding what needs to be conserved. Taking note of geographical locations, history and the dangers facing Kenya’s Heritage Sites prompts action.

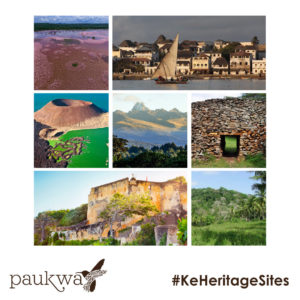

Our Heritage Sites include a stone walled structure, a mountain, a desert lake with three national parks, a fort, a coastal forest, a Swahili town, and three saline Rift Valley lakes. They have each been recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as places of outstanding universal value. They are one of a kind and thus should be preserved for future generations.

Then comes the follow up question: how do we get involved in on-going conservation efforts? Or how can we be advocates for preservation?

In a live audio discussion held on 22nd July 2021 on Twitter by Paukwa Stories, and contributors working with different institutions spearheading conservation measures shared that conservation begins by working with local communities. Current heritage sites have connections to local communities; communities that have valued these sites even before they gained international recognition. They therefore understand the importance of conserving them. The Mijikenda Kayas, for instance, are sacred to this community. The Mijikenda can trace their settlement in this forest site back to the 16th century. This is an example of a cultural site, but the same can be said for natural sites as well.

Image credit: Okoko Ashikoye

The importance of Lake Bogoria to the Endorois community that has lived around it for over 300 years cannot be overstated. In 1970, the Kenyan government evicted this community from their ancestral land to create a game reserve, but the Endorois fought to have this decision overturned. On 2nd February 2010, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights declared the expulsion of the Endorois from their ancestral land illegal. This landmark decision represents the first time that an African indigenous people’s rights over traditionally owned land was legally recognized. It is a beacon of hope for other communities that are fighting to maintain their spaces as their own. But all of this could have been avoided had the government worked with the community as opposed to working against it.

Image credit: Air Pano

Development is an important aspect of modern society. However, when it comes to heritage sites it is important to tread the fine line between development and conservation. Every historical site has an important story to tell. Heritage sites create a real connection to our past and help us understand our roots. Lamu Old Town is one such site, but because of development, it stands the danger of being delisted. This, again, circles back to community involvement. Providing the community with information needed to protect these sites empowers them to be the front liners in conservation efforts.

Our greatest takeaway from this conversation was that communities give sites their importance. As such, a site does not need to be recognized by UNESCO for it to be a place of value. We can decide what is of value to us, and in our own little ways, begin contributing to its sustenance.

*

We would like to thank Samia O. Bwana from HiiStoriya, Purity Kiura from National Museums of Kenya, and Joseph King from The International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) for their contribution to this conversation.